Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

Watching the Space Race: Well, One Worked

Posted by

Karina Fabian

|

Labels:

history of american space,

pioneer program,

space race history,

walt staples

by Walt Staples

Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

It was two days after my ninth birthday that NBC's Chet Huntley announced yet another Pioneer mission failure. This time the third stage and the Pioneer lunar orbiter (Pioneer P-3, fifth in the series) were stripped off of the Atlas-Able launch combination by the slipstream after its aerodynamic shroud (read nosecone) was shredded. At the time, this didn't particularly upset me. Watching American efforts since Vanguard had taught me that most American launches go wrong—it was like me and spelling tests.

The watching the early Pioneer program was rather like watching the progression of Commanders of the Army of the Potomac during the War Between the States/American Civil War (“Our own beloved General George Mead is now Commander; the fifth if you keep count as they go by.” – Buster Kilrain in the movie, “Gettysburg”). Unfortunately, this fifth Pioneer launch was a dud just as were the previous four. NASA would have to launch an eighth before they found their George Mead.

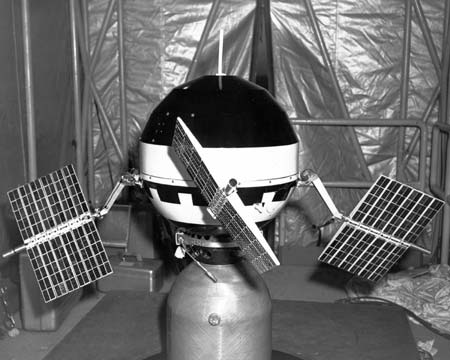

Four months later, something weird happened at Cape Canaveral. At 13:00 GMT on 11 March 1960—a Pioneer launch actually worked. Pioneer 5 (eight in the series), known to us kids as the “paddle-wheel satellite,” was inserted into a solar orbit by its Thor-Able launch vehicle.

We referred to the 75 pound (34 kilo) satellite as the “Paddle-wheel Satellite” for good reason. Protruding from its 26 inch (66 cm) diameter sides were what could only be described as four “paddles.” The paddles in reality were solar arrays to power the four science packages on board. The four packages consisted of an instrument to detect charged solar particles, a magnetometer to measure magnetic fields of both of Earth and those in interplanetary space, a cosmic ray detector, and a micrometeorite impact detector. The solar cells were so few that collected data had to be saved and sent to Earth in four 25 minute spurts spread over 24 hours. The signals were received at England's Jodrell Bank Observatory (a place familiar to Dr. Who fans) and the Air Force's Hawaii Tracking Station at Kaena Point on Oahu (originally built for the Discovery/Corona program of reconnaissance satellites). The last data was received on 30 April 1960 and the last signal of any kind was received at Jodrell Bank on 26 June 1960 when Pioneer 5 was 22.5 million miles (36.2 million km) from Earth.

The results from the instrumentation was mixed. Magnetic fields were successfully measured, as was cosmic radiation and particles from solar flares. Unfortunately, the micrometeorite counter was overwhelmed with hits.

Two more lunar Pioneer missions returned to the project's accustomed trend with failures. The last being Pioneer Z, on 15 December 1960, when the upper stage of its Atlas-Able failed.

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

0 comments:

Post a Comment