Watching the Space Race: An Orb in Space

Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Walt's Watching the Space Race will continue December 27 and 30th. In the meantime, I thought you'd enjoy some retro Christmas cards made in Russia during the Space Race Era. You can find more here.

Watching the Space Race: Well, One Worked

Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

Watching the Space Race: Hidden Under the Tree

Thoughts on Manned Space #3: Don't Leave it to the Government

When it came to colonizing the New World, the governments of Europe had a big role in support, but when it came down to it, it was the commercial businesses and private citizens that ensures a permanent presence. If we're going to have the same kind of success in space, we need to have the same kind of participation, but it seems many people have forgotten that. Thus, let me present three reasons I see why we cannot leave space exploration to the government:

#1 The government has other priorities. Let's face it, the government has gone waaay beyond what the founding fathers intended, and we have a huge deficit and a lot of conflict as a result. What's the government's job in space, then? I'd suggest it's pretty much the same as it is on Earth--protecting the rights and freedoms of its citizens. Step one is establishing a presence in space--a permanent, sustainable presence. Just like with colonization of the New World, that doesn't mean only government employees or government-funded exhibitions, however. It does mean being ready to support even defend its citizens who go fare beyond the Earth. (Sorry, Space is for Peace supporters--I want space to be peaceful, too, but not every nation is going to support that, and if they challenge our presence, we'll need government presence to defend us. And that can be diplomatic as well as military.) However, government role is support of space endeavors and the rights of its citizens in space--not taking on the whole manned space program itself.

#2 Governments are more swayed or stymied by public opinion. Sure, commercial companies need to have a good image, but frankly, as long as they are pleasing their customers, the rest of the world can take their business elsewhere. Governments, unless they're totalitarian and can do what they please, thank you very much, can be swayed by opinions like this one: End Space Exploration Now. And in fact, our government HAS been swayed by opinions like this, which is why the space program has had such rocky fits and starts. Unless space exploration can directly "feed the hungry children" or cut unemployment by several percentages (I don't think they'd be satisfied with anything less) or solve the deficit or whatever the political crisis du jour is, it will not get a gung-ho kind of support we got when first putting a man on the Moon. Without gung-ho support that crosses political parties, we're not going to get a long-lasting coherent government space program.

#3 Governments aren't big on innovation. Yes, I know it's one of NASAs missions to promote new technology, but as a counter, may I present a space shuttle that had to be decommissioned because they couldn't find parts, a bomber fleet in which today's pilots are literally flying their grandfathers' airplanes, a fighter program that might be canceled because Congress won't fund it... Or let's talk cost overruns because of the way the contracting system works in the government. Or maybe how a new administration can kill a program media res and replace it with his own great idea...which may or may not survive the next election.

The fact is, the government isn't interested in profit or product the way a commercial industry has to be. So when it comes to technological programs, they are looking as much at will it make jobs and promote themselves or their party as will it create a product that will get the job done--and then how to create the next one to do it cheaper, easier or more safely. I'm not trying to put down NASA or government contractors like Lockheed Martin, but they are at the mercy of the political system, which really is more conducive to road repair than rocket building.

Government has a role in space exploration. It can do some things commercial industries, especially fledgling ones, can't. However, if we want a real, sustained presence outside the atmosphere, it will take more than the government.

The Dragon's Going to ISS Feb 7!

Hooray! SpaceX has a launch date for the Dragon Feb 7! The NASA Press release is here, but here are the highlights:

* The Dragon will first do a fly-by at about 2 miles away from the station in order to check its sensors and other systems needed for a safe docking.

* When the Dragon docks, the ISS will use its robotic arm to assist. (It doesn't say why that is so. I had thought from the videos that it would dock on its own.)

* SpaceX is, of course, the first commercial craft to dock with the International Space Station, so this is history in the making.

* SpaceX has completed 36 of 40 of the milestones disctated to it under the COTS agreement, for which it will receive a total of 288 million dollars. (To compare, the space shuttle Endeavor cost 1.7 billion dollars.)

Of course, the next step for the Dragon and SpaceX is to finish the modifications that make it manned-approved. SpaceX has suggested that the Dragon is manned capable. However, there are certain modifications, like an escape system, that NASA is requiring. (Not a bad idea considering the Shuttle disasters.)

Forbes Magazine says that in light of the problems that the Russians have been having with their program lately, getting commercial flights going. Considering the latest report on how they were working on Phobos-Grunt, including soldering it while full of highly explosive rocket fuel, I'm even more glad to see us making progress toward domestic services. I had been seeing reports that the Dragon's maiden flight might get pushed off as far as April. I wonder, did the Phobos-Grunt failure (and subsequent revelations) perhaps nudge someone in the bureaucracy to accelerate the schedule?

According to NASA, SpaceX has really put their nose to the grindstone to fix problems NASA pointed out: "SpaceX has made incredible progress over the last several months preparing Dragon for its mission to the space station," said William Gerstenmaier, NASA's associate administrator for the Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate. There's oddly nothing on SpaceX's website about this yet. I wonder if their web guru is on vacation, or if the small company had just been putting its efforts elsewhere. Whichever, congrats to SpaceX and Happy Flynig!

Watching the Space Race: Why All of the Sudden?

For more information: http://www.nationalacademies.org/history/igy/

Space Coolness--LIVE

Today, I present to you some fun space links to see what's happening right now:

See what the International Space Station Sees: Live link at http://www.nasa.gov/multimedia/nasatv/iss_ustream.html

|

| Hey! I can see my house from here! |

Remember the Voyager probes? We're still discovering stuff from them! They're in the heliosheath (the outer part of the heliosphere where solar wind is slowed by pressure from interstellar gasses--about 80 times the distance from the sun that the earth is! You can exactly how far they've traveled here: http://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/where/index.html

|

| Can you hear me now? |

|

| No, John Carter is not your tour guide. |

| Sadly, it didn't let me design this. Sigh. |

Here's you chance to be an astronaut!

Serioiusly! NASA has opened up applications for astronauts. Get the details here: http://astronauts.nasa.gov/.

You have until January 27, so brush up those resume's now.

There's no guarantee that as an astronaut, you'll actually go into space. Instead, you get to go around doing PR work for NASA, along with lots of ground-based work. In fact, do you know what they call astronauts who never get off the Earth?

Incidentally, people will be applying via the military as well. Rob's already getting the forms from the manpower folks. He wants to be the next Fabian in Space.

| Not a penguin. |

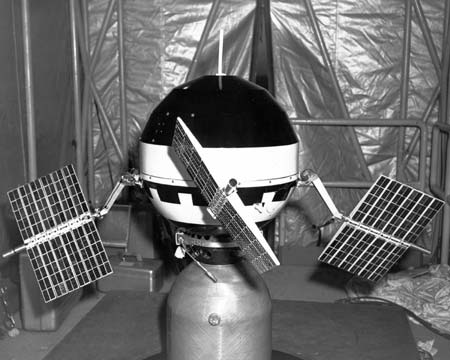

Watching the Space Race: Finally! America Enters the Race with Explorer

by Walt Staples

thoughts on Manned Space #2: Find the Water

Curiosity is on its way, with the mission of analyzing rocks along the Gale crater for signs of organic (carbon-based) compounds. It’s unique in that it’s a change from NASA’s usual Mars missions, which usually sought water or evidence of water.

We’re starting to find lots of evidence of water on other celestial bodies, from Mars to the moons of Jupiter to far-off planets. This is promising if we ever want to reach beyond our own planet, much less the solar system. But just what’s the big deal about water?

Most obviously, we need water in order to survive—to drink, to cook, to wash. It’s both a universal solvent and a catalyst for a lot of chemical reactions, so it’s important for experiments as well as daily living. Water is also useful as rocket fuel—seriously!

Quote

Driven by a need to use a fuel that can be produced on water-bearing planets and pressured by environmentalists, researchers are working to develop a new type of rocket fuel, made of a frozen mixture of water and “nanoscale aluminum” powder with the thickness of 80 nanometers, that could be easily manufactured on the moon, Mars or any other planet having water on it.

The aluminum powder, aka ALICE, can be used to launch the rockets into their orbit, fuel long-distance space missions and generate hydrogen for the fuel cells, says Steven Son, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Purdue University, who is working with NASA, the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and Pennsylvania State University to develop ALICE, used earlier this year to launch a 9-foot-tall rocket.

“ALICE might one day replace some liquid or solid propellants, and, when perfected, might have a higher performance than conventional propellants,” said Timothee Pourpoint, a research assistant professor in the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics. It’s also extremely safe while frozen because it is difficult to accidentally ignite,” he added.

A much longer term concern is removing water from this planet to service life on other planets.I think Douglas Adams summed up the problem best in Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy:

After a while, the style settles down a bit, and it starts telling you things you actually need to know, like the fact that the fabulously beautiful planet of Bethselamin is now so worried about the cumulative erosion caused by over 10 billion visiting tourists a year that any net imbalance between the amount you eat and the amount you excrete whilst on the planet is surgically removed from your body weight when you leave. So every time you go to the lavatory there, it's vitally important to get a receipt.

The Earth's atmosphere keeps water locked into a continuous system—remember fourth grade science? Other planets with less atmosphere don’t have that. In fact, there’s a theory that part of the reason Mars no longer has surface water is that it all sublimated into space. So we have to be careful, even with the water we find, to make sure we don’t lose it. (Which goes back to the recycling. Don’t think about where the water’s been.)

Naturally, water is also one of the primary indicators of biological life, and while we might not find little green men, we are more likely to find little green microbes and other small life that can live in extreme conditions. (Called Extremophile life, and you can find it on earth, too—even in nuclear waste!) This could be a boon, if we can find and cultivate native food sources, or a bomb, if we come across something dangerous to humans. (Remember the Andromeda Strain? The trailer is hokey, but I saw it again last week while doing research. Still a freaky movie worth watching, even fourty years later!)

So finding indigenous sources of water is another vital step toward establishing a manned presence off the earth. That we have found it is a promising sign. Now, we need to figure out how to best to harvest, protect and use it.

In the meantime, I'm thirsty. Time to get a drink.