Watching the Space Race: Suborbital Radio Days

Posted by

Karina Fabian

|

Labels:

alan shepard,

freedom 7,

space race history,

the space race,

walt staples

by Walt Staples

It was the merry month of May, and I was greeting it in my usual fashion—that is to say, coughing my head off. There is something of early May that doesn't like me and, I must admit, I ain't real fond of it either. My mother and I had pulled into a parking place outside Springfield Pharmacy to pick up a new prescription which was sure to cure what ailed me (yeah, right, just like the last six or eight) and a model kit and a couple of comic books to sooth my un-fevered brow (okay, the lady knew the way to a grumpy ten-year-old's heart).

We had been half-listening on the old Buick's radio to the chatter from Cape Canaveral as the newsmen tried to keep each other and their audience from sliding into terminal ennui while yet another hold on the countdown crawled by. NASA had been trying to get Freedom 7 off the pad since the 2nd of May, and the cancellation the day before hadn't inspired much hope in us that the bird wouldn't continued to hang fire on this Friday morning, 5 May 1961. Just as my mother reached for the key to cut the engine off and put the broadcasters in Florida out of their misery, somebody said, “We have go at countdown.” The two of us leaned back against the wide bench seat; okay, we'd play along a tad more. We were rewarded with “T-minus ten-nine-eight-seven”—and on down to liftoff. We sat entranced staring at the front of the AM radio with its missing station selection button.

It seemed like a couple of years later that the announcer reported “splashdown”--a new word--for Alan Shepard, the first American to “ride the stack,” and that both astronaut and Mercury capsule were safely aboard the carrier. At that point, life returned to its more-or-less normal course--at least until the next launch.

The U.S. had been doing a slow burn since Yuri Gagarin, a Soviet Air Force senior lieutenant, had become the first man to orbit the Earth on 12 April 1961. It was galling to always be following the Soviets' tracks. So far, the closest an American had come to spaceflight, were the pilots of the X-15 program out at Edwards AFB skipping along the vague boundary between the atmosphere and space. It was spaceflight, sort of, but pretty much unsatisfying to the citizenry.

At 09:34 Eastern Time, we finally got a biped that didn't chatter and pick up things with his feet into space, if only for a few minutes. The launch vehicle was one of von Braun's Redstones (the basis for the Jupiter-C/Juno 1 that lofted Explorer 1 into orbit three years before). The entire flight lasted a bit over 15 minutes from launch to splashdown off the Bahamas. The Mercury capsule measured 81 inches (32 cm) long by 74.5 inches (29.5 cm) in diameter at its widest--the reentry heat shield--and had sat atop the 63 foot (19 m) tall Redstone.

The word is, that originally, NASA was going to go for a totally automatic flight system like the reported Soviet practice, the astronaut more along for the ride rather than piloting the Mercury capsule—the “Spam in a can” school of spaceflight. There are various versions of why this was changed, but Alan Shepard was able to control the Freedom 7's movements in three axis. The flight had lasted 15.5 minutes, traveled 302 miles (486 km), and reached a max altitude of 116 miles (187 km). The time from splashdown to astronaut and capsule arriving on the USS Lake Champlain's deck was around 11 minutes—a speedy performance which would not be equaled again any time soon on later flights. Especially not with Gus Grissom's following suborbital Liberty Bell 7 flight on 21 July 1961or that of the first American to orbit, a “Mig-Mad Marine,” five months after that.

Read User's Comments0

Things to Know About Space for 2012

Posted by

Karina Fabian

|

Labels:

chinese in space,

commercial space,

elections and space,

politics and commercial space,

presidential elections and the space program,

space in 2012

|

| Art by Marina Muscan |

by Walt Staples and Karina Fabian

Happy New Year! 2012 looks to be an exciting time for space. We'll see commercial and Chinese presence growing in the manned space arena, and unmanned space exploration is forging ahead. Of course, the political climate may change with the elections coming. So here are are a few articles to get you ready for 2012:

Snapshot of Most Anticipated Events for 2012: Commercial space flights to support manned space, Chinese space labs, moon mapping, light sails, asteroid and Mars missions and secret space missions (and you thought the Shuttle was dead.) Space.com takes you on a whirlwind tour of what to expect this year.

China has big plans for space: Communist countries have always been big on "Five-year-plans," and China has announced its plans for space through 2016. It includes more launches "space freighters" and orbiting spacelabs. The article notes that space is a matter of national pride, but I think the Chinese see a potential market as well.

Presidential Candidates' Stands on Space: Speaking of "five-year-plans," wouldn't it be nice if the US could hold onto a plan for more than a few years? Obama made a radical move by putting near-earth space in the hands of commercial industries and turning the government focus to farther out. Question is, will it stay that way in the next election? This article shows the space policy stances of the presidential candidates. Between you and me, I don't see why there has to be opposition on this issue. Promoting private industry is a Republican thing--why not take the stance that "Well, since Obama sees things our way on this..."

Watching the Space Race: The World Got Smaller

by Walt Staples

Note from Karina: This one should have posted on the 30th. Hope you've been enjoying the walk down Memory Lane with Walt. We'll resume the normal schedule of "Watching the Space Race" next week, with Walt's posts resuming Jan 7 and going on Saturdays until he runs out of events. (He'll never run out of interesting things to say.)

There are few things as exasperating as receiving orders to break off an operation just as you're ready to take the other guy in the flank. Unfortunately, when Aunt Geneva called your name from the backdoor, an immediate truce ensued. This July afternoon in 1962 was no different. I dropped the muzzle of my weapon of choice, a .45 Thompson submachine gun—one of the finest examples of Mattel's firearms production—and told Tommy Huddleston I'd see him later.

Note from Karina: This one should have posted on the 30th. Hope you've been enjoying the walk down Memory Lane with Walt. We'll resume the normal schedule of "Watching the Space Race" next week, with Walt's posts resuming Jan 7 and going on Saturdays until he runs out of events. (He'll never run out of interesting things to say.)

There are few things as exasperating as receiving orders to break off an operation just as you're ready to take the other guy in the flank. Unfortunately, when Aunt Geneva called your name from the backdoor, an immediate truce ensued. This July afternoon in 1962 was no different. I dropped the muzzle of my weapon of choice, a .45 Thompson submachine gun—one of the finest examples of Mattel's firearms production—and told Tommy Huddleston I'd see him later.

I wasn't sure why my Aunt wanted me. We'd had dinner; it was sometime after two and supper was usually at six. I'd learned during the summer that I stayed with them, that she and my Uncle Jack were very punctual folks.

She was drying her hands on her apron as I stepped up on the porch. “Come on in; there's going to be something on television we need to see.” This was a bit out of the ordinary. Usually, in the afternoon we might watch the “Channel 10 Matinee for an Afternoon” together, but that came on at two and the cat clock on the kitchen wall showed a few minutes until three.

“What's on?”

Her answer nonplussed me. “Pictures from Europe.” I raised an eyebrow (a bad habit for an eleven-year-old when dealing with adults). Reading my mind, she continued, “No, I don't mean pictures like we usually see. I mean live pictures, not on film. They're going to be showing pictures of what's going on right now, this minute. They're sending them through that satellite, Telstar.”

The two of us settled on the couch. At three sharp, we entered the world of real-time international TV. An American TV news anchorman (at this point, I frankly can't remember whether it was NBC's Chet Huntley or CBS's Walter Cronkite—or both) welcomed the viewers. I remember seeing an American Flag, the Statue of Liberty, and—I think—Mount Rushmore. This was replaced by a tweedy gentleman who said in a plummy BBC accent that he was speaking from Brussels. The picture switched to Paris and the Eiffel Tower. The broadcast closed, as I remember, with a shot of the huge white bubble that enclosed the antenna in Andover, Maine. Interestingly, the pictures from the American side were crystal-clear (at least as judged for that time), but the pictures from Europe rippled as if seen through heat waves or water. The pictures we watched were in living black and white—whether they were broadcast in color or not, I don't know; my aunt and uncle, like most at that time, owned a black and white set (it wasn't until 1964 that my father bought a RCA color console model—the local TV repairman had to study a week and a half before he could adjust the colors that had been scrambled on the trip from the store in Roanoke over the mountains into the wilds of West Virginia—he didn't charge us because of the learning opportunity). [If anyone reading this knows whether or not the broadcast was in color, I'd appreciate them leaving the answer in the “Comments.”]

*

Telstar 1 was owned by AT&T and developed by Bell Labs (part of the Bell Telephone System--”Ma Bell”). It was lofted by a NASA Delta rocket which limited its size to a 34.5 inch (87.6 cm) sphere. The satellite turned the scales at around 170 pounds (77kg). It was powered by solar cells producing a staggering 14 watts and was spin-stabilized.

Telstar first broadcast a picture on 11 July 1962, a nonpublic “Is this thing working?” broadcast. The first public broadcast, the one my aunt and I marveled over, was on 23 July 1962 at 15:00 EDT. As it was in a non-geostationary orbit, unlike the norm for communications satellites these days, Telstar 1 was only above the horizon for 20 minutes during each 150 minute orbit.

Telstar 1 established several firsts besides being the first rebroadcasting telecommunications satellite. It was also the first privately owned payload launched by NASA . It was the first satellite, to my knowledge, to have a song named for it (Joe Meek's instrumental which is on the first record I bought with my own money, “The Ventures Play Telstar and the Lonely Bull”--which I'm listening to as I write this). It's also the first satellite to have a soccer ball named for it, Adidas's design for the FIFA World Cups competitions—the black and white one that most of us in the U.S. think of when the word, “soccer ball,” is mentioned.

Telsar 1 continued in service routing TV, telephone, and fax and data traffic until a number of its transistors were fried by Van Allen Belt radiation excited by high-attitude detonations during both American and Soviet nuclear testing. It first went off the air in early December of 1962, was resuscitated a month later, and finally died on 21 February 1963. At last word, Telstar 1 is still orbiting the Earth, a victim of the Cold War.

Watching the Space Race: An Orb in Space

by Walt Staples

I must admit to a disgusting family trait—we're morning people. I was actually awake and alert when I saw the balloon floating in space that warm August 1960 morning. I was up at my usual 05:00, had eaten breakfast (found the dinosaur in the cereal box—same one as in the last three), and was waiting for Sunrise Semester to come on TV. The Friday before, a photo of a huge silver balloon in a hanger was shown on NBC's Huntley and Brinkley (I forget which one did the story). Across the front was “N.A.S.A.” in equally huge letters—they didn't lose the periods until years later. According to the report, a radio signal had been bounced off the balloon, Echo 1. Standing in the darkness of our backyard, I watched the horizon over the small pine thicket. After some 15 or 20 minutes, a bright point of light, about the magnitude of Aldebaran (0.87) crawled into sight. I watched until it disappeared over the ridge of Colonel Coon's roof across the street. Then I went back in and watched part whatever of a lecture on the Peloponnesian War—I think—before getting ready for the bus to summer day camp.

*

Project Echo involved the launching of a self-inflating mylar balloon into LEO (Low Earth Orbit—100 to 1,240 miles/160 to 2000 km). Upon reaching orbit, the balloon would inflate and ground stations would send microwave signals to it, and the signals would be reflected back to another ground station.

What is referred to as Echo 1 was actually Echo 1A. The original Echo 1 was lost on 13 May 1960 when the Air Force Thor-Delta lofting it missed orbit because the attitude control of its upper stage went sour. Not a way for a launch vehicle to impress on its debut flight. At 09:39 GMT, on 12 August 1960, another Thor-Delta got 'er done and put the latest incarnation of Echo 1 into orbit. (That day in August 1960 was a particularly hazardous day for birds. At 13:00 GMT, an Air Force Atlas suborbital test was also launched from Cape Canaveral; followed at 18:28 GMT by a test of the Polaris submarine-launched missile by the Navy from their end of the Cape. Meanwhile, the Air Force was launching a Kiva-Hopi sounding rocket from the Pacific Missile Range on California's Point Arguello*. On the other side of the world, the Soviets were test-firing a R-12 Dvina medium range ballistic missile from what would later be renamed “Baikonur Cosmodrome,” Kapustin Yar.)

Once in orbit, the balloon inflated to its full 100 foot (30.5 meter) diameter. A signal was sent up to it from JPL in Pasadena and bounced down to the Bell Laboratories in Homdel, New Jersey. Echo 1's silver surface was used to bounce TV, radio, and transcontinental and intercontinental telephone signals. Because of its large sail-area and tiny mass—about 90 pounds (180 kilos)--the solar wind had a noticeable effect on it. The larger Echo 2 (135 feet/41.1 meters) was successfully orbited aboard a Thor-Agena on 25 January 1964. Echo 1 reentered on 24 May 1968, while its sibling deorbited on 7 June 1969.

What was not mentioned at the time was another part of the missions. The pair of balloons were used to more accurately fix the location of Moscow to aid in targeting for ICBMs.

I remember standing in line at the East Springfield, Virginia, Post Office that December so that I could buy the commemorative First Class stamp the Post Office had issued on 15 December. First Class postage at the time was a whopping four cents—something my father grumped about quite regularly (the year before, it had skyrocketed from three cents).

* Another thing of interest about Point Arguello is that in 1923, seven U.S. Navy destroyers (part of a 14 ship formation on a speed run from San Francisco to San Diego) piled into the point at flank speed in fog. 23 crewmen were lost in the sinkings.

Merry Christmas!

Merry Christmas, everyone!

Walt's Watching the Space Race will continue December 27 and 30th. In the meantime, I thought you'd enjoy some retro Christmas cards made in Russia during the Space Race Era. You can find more here.

Wishing everyone a blessed Christmas and a terrific New Year!

Karina Fabian

Walt Staples

Watching the Space Race: Well, One Worked

Posted by

Karina Fabian

|

Labels:

history of american space,

pioneer program,

space race history,

walt staples

by Walt Staples

Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

Note from Karina: My kids are on Christmas holidays, and I just finished writing Neeta Lyffe, Zombie Exterminator 2: I Left My Brains in San Francisco, so it's the perfect time for a break. Walt, meanwhile, has so been enjoying his trip down memory lane, he's got several posts done for "Watching the Space Race." So for the next couple of weeks, you can join him in remembering the "Glory Days" of space travel. Enjoy!

It was two days after my ninth birthday that NBC's Chet Huntley announced yet another Pioneer mission failure. This time the third stage and the Pioneer lunar orbiter (Pioneer P-3, fifth in the series) were stripped off of the Atlas-Able launch combination by the slipstream after its aerodynamic shroud (read nosecone) was shredded. At the time, this didn't particularly upset me. Watching American efforts since Vanguard had taught me that most American launches go wrong—it was like me and spelling tests.

The watching the early Pioneer program was rather like watching the progression of Commanders of the Army of the Potomac during the War Between the States/American Civil War (“Our own beloved General George Mead is now Commander; the fifth if you keep count as they go by.” – Buster Kilrain in the movie, “Gettysburg”). Unfortunately, this fifth Pioneer launch was a dud just as were the previous four. NASA would have to launch an eighth before they found their George Mead.

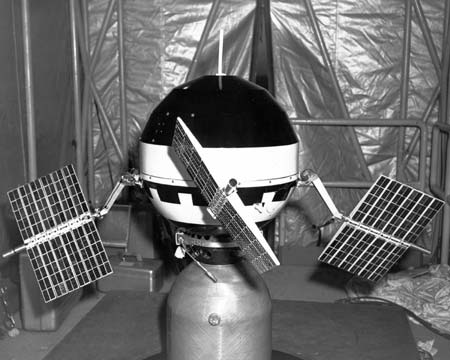

Four months later, something weird happened at Cape Canaveral. At 13:00 GMT on 11 March 1960—a Pioneer launch actually worked. Pioneer 5 (eight in the series), known to us kids as the “paddle-wheel satellite,” was inserted into a solar orbit by its Thor-Able launch vehicle.

We referred to the 75 pound (34 kilo) satellite as the “Paddle-wheel Satellite” for good reason. Protruding from its 26 inch (66 cm) diameter sides were what could only be described as four “paddles.” The paddles in reality were solar arrays to power the four science packages on board. The four packages consisted of an instrument to detect charged solar particles, a magnetometer to measure magnetic fields of both of Earth and those in interplanetary space, a cosmic ray detector, and a micrometeorite impact detector. The solar cells were so few that collected data had to be saved and sent to Earth in four 25 minute spurts spread over 24 hours. The signals were received at England's Jodrell Bank Observatory (a place familiar to Dr. Who fans) and the Air Force's Hawaii Tracking Station at Kaena Point on Oahu (originally built for the Discovery/Corona program of reconnaissance satellites). The last data was received on 30 April 1960 and the last signal of any kind was received at Jodrell Bank on 26 June 1960 when Pioneer 5 was 22.5 million miles (36.2 million km) from Earth.

The results from the instrumentation was mixed. Magnetic fields were successfully measured, as was cosmic radiation and particles from solar flares. Unfortunately, the micrometeorite counter was overwhelmed with hits.

Two more lunar Pioneer missions returned to the project's accustomed trend with failures. The last being Pioneer Z, on 15 December 1960, when the upper stage of its Atlas-Able failed.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)