Tuesday, I talked a little about the Saturn V and touched briefly on the latest replacement, the imaginatively named SLS (Space Launch System).

One of the things I wondered about was why, if we've already built something nearly as powerful, can't we do it again quickly? I came up with a few reasons: technology has advanced; safety standards have increased; and politics/government. The Oct 22 Space News offered up another point: budgets.

Okay, budgets are part of politics, but what I found interesting is that it's not just budget cuts that are affecting the SLS program, but the fact that the budget does not have room to increase when they need more.

"If you are a project manager, you know that the development curve wants to be a curve...So if you stack a development curve on top of a developement curve, you get a very acute rise in cost. One of the things (the SLS program managers) came to very quickly is we could probably afford one development at a time." --Todd May, manager of the SLS program office at NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center, quoted in Space News

Because of this, they have to move more slowly, going a piece at a time. That's one reason why they won't make their first flight until 2017 and the first crewed flight until 2021--and they will be using a different booster by that time, too.

On the bright side, budget cuts are resulting in NASA cutting down on contractor oversight, which, according to Space News, means they'll lean more on industry standards as opposed to NASA tradition. That could be a good thing, and in fact, some companies (like ATK) say that will let them speed up production in some areas (reducing cost in the process.)

Government Spaceflight--why is it taking so long?

Space Studies Tuesday: Woe to the Loss of the Saturn V--NOT

There is so much interesting stuff in John Lewis' MINING THE SKY that I may never touch on it all. However, he brought up the Saturn V, and since now and then, I hear people bemoaning the loss of the Saturn rockets, I want to address that.

The Saturn V took the Apollo capsules to the moon, but when the program died in 1973, the program was scrapped. In fact, a set of the plans were given to the Scouts for recycling (go OPSEC!) and two flight-ready rockets were relegated to lawn ornaments. (The last three Saturn 5 boosters, already build and paid for, were put out as lawn ornaments at Cape Canaveral, Marshall Space Flight Center, and Johnson Space Center, to rust into ruin..." pg 4, Mining the Sky)

|

| Well, not quite a lawn ornament, but you get the picture. |

The termination of the Saturn V program also had a stifling effect on the robotic exploration of other planets. In essence, we lost the ability to deliver larger, and in some cases faster, payloads elsewhere in the solar system.

Take, as an example, the 5,600-kilogram Cassini spacecraft, which was launched in 1997 and is now in orbit around Saturn. Its launching was timed so that after spending two years looping around the inner solar system to pick up speed, it could rendezvous with massive Jupiter for an additional boost that would send it to Saturn. All told, its flight time took seven years.

Had the Saturn V, modified with an appropriate fourth upper stage, been used to launch Cassini directly to Jupiter first, its flight time to Saturn could have been cut by more than half. In space, as on Earth, time is money, and the money saved could have been spent elsewhere.

Alternatively, for the same flight time, a vehicle of greater launching capacity can deliver a heavier payload. Take as an example the 480-kilogram New Horizons spacecraft, launched over a year ago to fly by Pluto in 2015 and eventually to explore the Kuiper Belt of icy debris that lies beyond it. Had it been launched on a modified Saturn V rocket, New Horizons could have carried a payload that was 15 times heavier and far more scientifically capable.

At this point, bringing back the Saturn V is not a good idea. In addition to being technologically old, it wasn't build to be cost-effective. According to NASA, the cost of one Saturn V, including launch, would be $1.17 billion (SP-4221 The Space Shuttle Decision, adjusted to inflation in an article in Wikipedia). We no longer have the "Just git 'er done" attitude of the Space Race of the 60s. Now, we have a stronger focus on expenses and safety.

More important than the rocket itself, however, is the attitude that the scrapping of the Saturn V represents.

As Lewis notes, this marks a significant turning point in the space program. Most importantly, it shows how little interest we as a nation had in continuing our space-based endeavors once we'd "won" the Space Race. (Russia, incidentally, dropped out once they saw the Saturn V program was outpacing their G-class rockets. It's pretty obvious men walking in space was more about men posturing on Earth.)

NASA at the time had some plans for a Moon colony, but overall, people did not have a drive for space exploration, and we've never had a long-term plan--or even long-term aspirations, just some nebulous dreams. We depended on the government to fulfill that dream, but when other voter-directed or politically expedient priorities arise, the long-term focus drops. The Shuttle and the ISS were restarts on that track, but just like the station, we ended up going in circles for thirty years. I don't think the powers that be of the time really thought about what the station could accomplish in the bigger manned space mission--or if they did, they lost it fast. We started to take a step outward with the Ares rockets and a moon-based mission, but it was scrapped. The SLS is in preliminary design phase, with the alleged mission of Mars, but who knows if that will survive an election?

Fortunately now, we are seeing a growing civilian interest, and not just as spectators or NASA supporters. From bloggers to businessmen, we are looking to space as more than bragging rights or national pride, and as a result, we'll have more communities upholding the long-term goal of manned space. The attitude that made the Saturn V is gone, and I hope the era of a post Saturn V world is ending as well. We're ready, technologically and in some ways, economically, to embark on a new era--a little slower, perhaps, but hopefully a more sure era of getting man beyond the Earth and into the exciting new frontier.

Space Studies Tuesday: A change in direction--Mining the Sky

|

If anyone is still following Space Studies Tuesday, you'll notice I've skipped a couple of weeks. I can claim sickness then the MuseOnline Writers Conference, but the fact of the matter is, as valuable as the JPL course information is, it's not especially interesting to blog about, and lately, it's become a drudgery. I plan on finishing the course, and I invite you to do the same--on your own.

However, I like the idea of Space Studies Tuesdays, and still want to study the NSS papers with you. I think there will be more room for discussion and exploration. In the meantime, however, I picked up Mining the Sky by John S Lewis. This was actually written in 1996, and I'm sure some things have changed since them, not the least of which is the founding of Planetary Resources. Nonetheless, I'm only three pages into it--the Preface!--and it makes me want to blog!

Mr. Lewis beings with a discussion of American industry and the conflict between pure research and end-of-quarter ledgers. Essentially, pure research doesn't pay off in the short term, and is thus easily cut by industries looking at improving short-term profits by cutting expenses. Of course this is like counting beans without thinking about where future beans will be planted, as Lewis puts it. This, of course, feeds into my personal stance that we cannot depend on government programs to get us into space on any long-term basis. After all, with a trillions-dollar debt and a government that changes every two years (because of congressional elections), long term thinking is fiscally and politically difficult. Ah, but here's the sentence that made me put down the book to blog to you:

"In a very real sense, scientifically and technically literate MBAs could save American Industry."I don't think we have to take "MBA" literally, but think about the people who are starting up many of the space industry companies today: entrepreneurs who sometimes made billions in some other industry (Paypal, Google, Microsoft...) who have turned their attention and their finances toward a longer-term goal, manned space.

But, Karina, they're not out there for pure research either; they're looking for profit. Absolutely true, but one feeds the other, which is another point Lewis makes: we need "a judicious balance between long-term basic research, short-term applied research, engineering development of products, and commercialization of new products." As I return to looking at space companies, I'll be looking for those elements.

In the meantime, back to the book! If you want to read along with me, you can find it on Amazon http://www.amazon.com/Mining-Sky-Untold-Asteroids-Planets/dp/0201328194 or B&N http://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/mining-the-sky-john-s-lewis/1111983588.

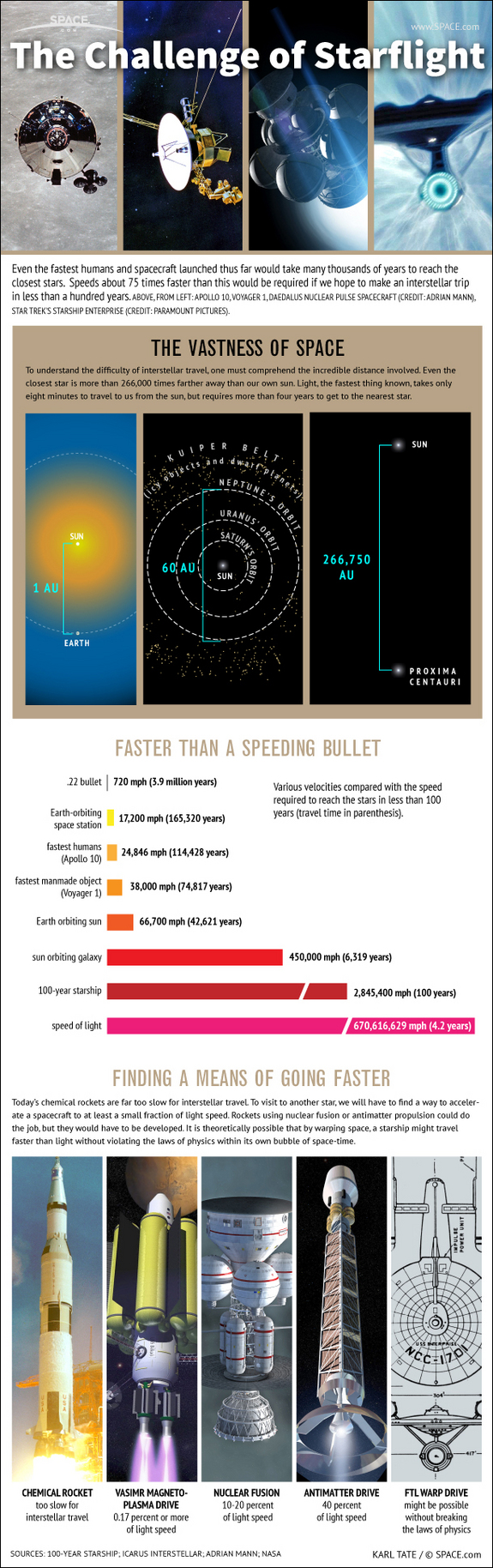

Inforgraphic on Interstellar Travel

I'm at MuseCon this week, talking writing with other fantastic people at all skill levels. Got this nifty graphic for you, courtesy of space.com

Source SPACE.com: All about our solar system, outer space and exploration